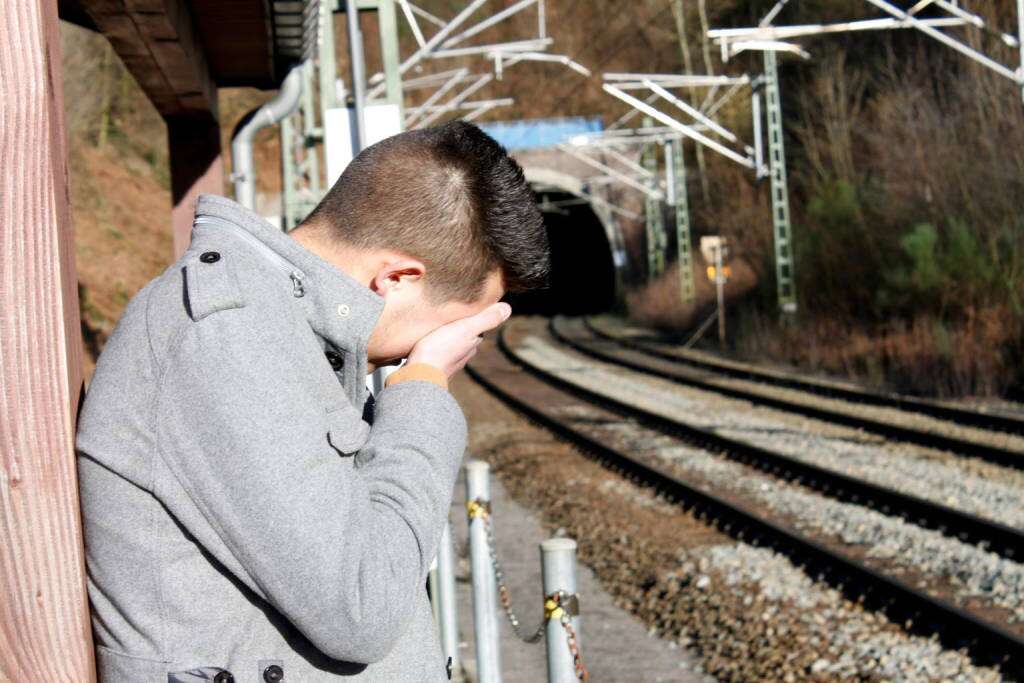

With youth suicide rates rising from the mid 2000s and astonishing increases in psychiatric drugs being prescribed, where have things gone wrong with the handling of youth mental health?

Suicide statistics going the wrong way

Looking at statistics for the youth mental health sector in Australia finds a situation where statistics are going in the wrong direction. Suicides of persons aged 15 – 24 are on a rising trend since the mid-2000s.

Breaking these statistics down finds the same trends in all age subgroups available, i.e. 14 and below,15 – 17 and 18-24. None of the age groups were found to have an improving trend, i.e. fewer suicides.

In trying to get some idea of more recent data it was found that in 2021 suicide remained the leading cause of death among people aged 15–24 (37%). 1

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Suicide and Self-harm Monitoring National Mortality Database—Suicide (ICD-10 X60–X84, Y87.0))

Suicides by age groups

Yet, more and more youth psychiatric drug prescriptions

At the same time as suicide statistics rising, there have been astonishing increases in psychiatric drug prescriptions for young people.

Unfortunately, statistics of prescriptions for various age groups do not go back as far in time as suicide statistics do. However, the following graphs give some idea over seven years of continually rising prescriptions.

With all of these drugs being given to Australia’s youth where are the indications of improved mental health?

(Source: Australian Institute of Healthy and Welfare. Mental health services in Australia: Mental health-related prescriptions)

Antidepressant prescriptions for ages 0 – 24

Prescriptions for antidepressants from 2014 to 2020 rose by 63% to 115, 482 for those aged 0 – 17 and rose by 40% to 246,511 for those aged 18 – 24

Antidepressant prescriptions by age groups

Antipsychotics prescriptions for ages 0 – 24

Prescriptions for antipsychotics from 2014 to 2020 rose by 24% to 22,081 for those aged 0 – 17 and rose by 23% to 246,511 for those aged 18 – 24.

Antipsychotic prescriptions by age groups

ADHD and cognition stimulant prescriptions for ages 0 – 24

Prescriptions for ADHD and cognition stimulant prescriptions from 2014 to 2020 rose by 87% to 144,078 for those aged 0 – 17 and rose by 86% to 23,823 for those aged 18 – 24.

ADHD and cognition stimulant prescriptions by age groups

What happened in the mid 2000s?

Any analysis of the youth suicide statistics could not ignore the rise in suicides beginning in the mid 2000s.

While certainly not the only influence on youth mental health, the major government-funded program to address this area; ‘headspace’ was launched in 2006.

Despite hundreds of millions of dollars spent on headspace, has it actually improved youth mental health and how to reconcile increased suicides?

‘headspace’ is the major Australian government funded program designed to address youth mental health using technologies developed by Orygen Youth Mental Health, under Patrick McGorry. ‘headspace’ as of March 2022 operates 145 services and some 14 Youth Early Psychosis Programs in every state in Australia.

‘headspace’, a closer look

In taking a closer look at ‘headspace’ there are several indications that something isn’t right.

A recent study of more than 1,500 persons attending ‘headspace’ and specialized youth mental health services located at Sydney University found:

“Two in three young people with emerging mental disorders did not experience meaningful improvement in social and occupational functioning during two years of early intervention care”.

F Iorfino et al Social and occupational outcomes for young people who attend early intervention mental health services: a longitudinal study. 2021. 2

Reviews by peers have highlighted the lack of effectiveness of the ‘headspace’ and Youth Early Psychosis programs:

“Unfortunately, the data do not look good, with headspace producing clinical outcomes similar to those seen in untreated control groups”

AF Jorm

A 2015 independent review of the ‘headspace’ program was less than glowing in terms of the program’s effectiveness:

“While some evaluation findings are mixed, results show that there are small improvements in the mental health of headspace clients relative to two matched control groups.”

Hilferty, F. et al . Is headspace making a difference to young people’s lives? Final Report of the independent evaluation of the headspace program. 2015. 3

“The findings of that study should have triggered alarm bells, according to Mr Patton who was involved in the 2015 review by the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of New South Wales.

“‘The single evaluation we have suggests that the gains are not that big, he said. ‘Adolescents who were attending Headspace were doing a little better than if they had not attended, but the difference was not huge.’

“The review found about 70 per cent of clients experienced an insignificant change or no change in their psychological distress levels.

“About 23 per cent had an improvement while 9.5 per cent experienced a noticeable deterioration.”

ABC. 2019. 4

And from AF Jorm, the co-founder of the Mental Health First Aide program:

“There are now more than 80 headspace centres in Australia, and the model is spreading internationally. Given this level of investment, we need to closely examine the benefits of headspace services. Unfortunately, the data do not look good, with headspace producing clinical outcomes similar to those seen in untreated control groups.”

AF Jorm Headspace: The gap between the evidence and the arguments. 2016. 5 and “However, it is important to note that this expansion has occurred in the absence of any evidence that headspace services are actually effective in improving youth mental health.” 6

Conclusion

There are obviously serious concerns with the state of youth mental health treatment in Australia. The most immediate conclusion from these statistics is that the enormous rate of prescription increase of psychiatric drugs is not helping things – and present the liability of the severe side effects they can produce.

The problems with ‘headspace’ seem to be already well known. The question really is what will it take to revamp it sufficiently to produce actual results in this area and more than just “more drugs”. Or can it be salvaged at all?

As mentioned, ‘headspace’ isn’t the only area influencing youth mental health and these will require a look too…

Further references:

Antipsychotics – a horrible replacement for even worse alternatives

Chemical imbalance – psychiatry as a pharma marketing tool

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Leading causes of death

- Frank Iorfino, Joanne S Carpenter, Shane PM Cross, Jacob Crouse, Tracey A Davenport, Daniel F Hermens, Hannah Yee, Alissa Nichles, Natalia Zmicerevska, Adam Guastella, Elizabeth M Scott and Ian B Hickie. Social and occupational outcomes for young people who attend early intervention mental health services: a longitudinal study. Med J Aust. Nov 2021.

- Hilferty, F., Cassells, R., Muir, K., Duncan, A., Christensen, D., Mitrou, F., Gao, G., Mavisakalyan, A., Hafekost, K., Tarverdi, Y., Nguyen, H., Wingrove, C. and Katz, I. (2015). Is headspace making a difference to young people’s lives? Final Report of the independent evaluation of the headspace program. (SPRC Report 08/2015). Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Australia.

- ABC. 2019. Headspace is ‘easy for politicians’, but failing Australia’s youth, experts say

- AF Jorm Headspace: The gap between the evidence and the arguments. 2016 . Aust N Z J Psychiatry.

- AF Jorm How effective are ‘headspace’ youth mental health services? 2015.